This blog post explores our process of creating terminal connection, including the process of finding and settling on the full idea for the game as well as a few core discussion points that emerged during production. We have a ton of very spread out thoughts about this game and how we made it, but we did our best to organize them into at least slightly useful categories and frameworks.

Our Chronological Process

The bulk of the detail in this section focuses on the work we’ve done this semester and especially since the last project we wrote about, Aero-Dynamics. We want to briefly mention that, in retrospect, the entire year, including all of the smaller projects we worked on last semester, played a part in moving us towards terminal connection. A great deal of the ideas, approaches, priorities, and techniques that we discovered in those games are reflected in terminal connection, and we couldn’t have understood what we wanted to make and why without those projects. We’ve written about them extensively on the blog (and there is also a brief discussion on how the entire process contributed to our artistic voice in the Developing Voice section of Zach’s reflection). That being said, let’s dive in.

Moving Forward from Aero-Dynamics

After creating our first prototype for the semester, Aero-Dynamics, we knew that we needed to make some drastic changes in the ways we were exploring the topic of hyperreality. As we discussed in the blog post about that project, it entirely lacked the emotional resonance that we were striving for: we realized that we needed to create a game that really feels like navigating hyperreality. For Aero-Dynamics, we leaned into more conventional, safe storytelling techniques, but moving forward, we made a decision to get a lot weirder (after a helpful push from our professors). We took a great deal of inspiration from games like NaissanceE in the process of finding our approach, seeing ways in which evocative environments paired with pointed gameplay moments could very effectively evoke visceral emotions.

Another big takeaway from Aero-Dynamics was the core mechanic of the plane. In our testing, we found that there was definitely something interesting there: the experience of flying a plane had some core metaphorical resonance with the subject matter. We connected with the very open movement scheme where the player has freedom to move in any direction, but we immediately saw a need for more tension in the mechanic. We saw potential in the experience of trying to fly the plane along surfaces, and after some testing, settled on the core mechanic in which the plane needs to be close to surfaces to maintain and gain speed. This matched the tension of navigating hyperreality in always being uncomfortably close to things around you, always moving too fast or too slow to have entirely effective control of yourself and your movement through the space. It feels like you can go in any direction, but in reality, you have to interact with the environment in very specific, limiting, and uncomfortable ways. This felt right for us.

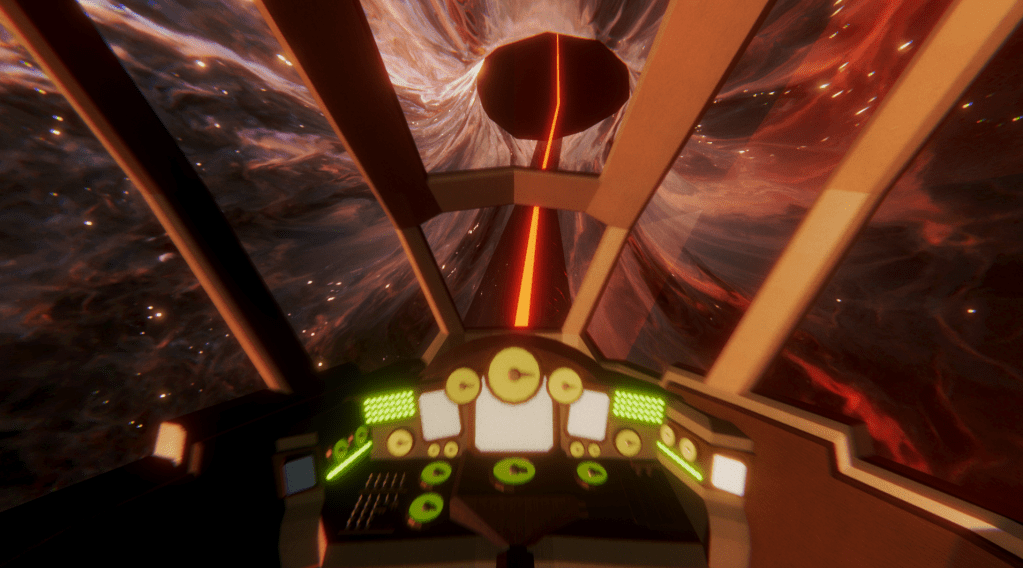

Another part of the experience of flying the plane that we really appreciated was the feeling of being incredibly small and vulnerable in comparison to the massive environments you must navigate. For us, this resonated with the experience of moving through other people’s subjective realities, feeling the force with which they are presented on the internet. One important factor in Aero-Dynamics was the idea that the player is in the position of someone growing up with the internet. While we didn’t keep this specific premise, we wanted to maintain (and lean into) the associated feelings of fragility and smallness. We quickly began testing different ways to find more depth in those emotions, and switching to a first person camera perspective stuck. It really evoked that feeling of sitting in a little tin can floating through the middle of a massive ocean, which is exactly what we were looking for.

Finding the Feeling

In order to start exploring the tools that we had at our disposal for generating more intense emotions (as well to provide an opportunity for personal ownership and artistic engagement), we split up and spent a few weeks ideating on and prototyping individual “levels” that would ideally elicit specific emotions related to hyperreality. We created presentations for each of our levels, workshopped them a bit together, then created working versions using the existing plane controller that we had set up. We then pieced the levels together with a simple tutorial and a vague title screen aimed at guiding the experience (at least a little bit). The presentations can be found here, and footage of the prototype, which we called Missing, is here (note: some music is missing from this gameplay footage due to copyright).

This process was absolutely huge in beginning to carve out the identity of the experience we wanted to create. There were certainly issues with the levels, but we started to see, at least in ourselves, a genuine connection to what we were making. We moved into a much more abstract space with these prototypes, and we really liked where they were going.

One of our main focuses was developing an approach to the environments and aesthetics of the game. We created some interesting places to explore, as well as interesting aesthetics to begin poking at what hyperreality feels like for us. Because this was our main focus though, we found a lack of engagement with the core mechanic of flight and proximity to surfaces. The first two levels (David and Zach) could be entirely completed with very little mechanical dexterity, which was an area we sought to improve. The final level (Austen) absolutely engaged with the core mechanics in its use of appearing and disappearing environmental pieces based on speed, but this use of the mechanic brought up a very interesting question: do we want the challenge of the game to be coming from dexterity challenges, navigation, puzzles, or something else? A deeper dive into how we approached challenges in the game is below in the “Challenges in the Game” section. Simply put, we definitely saw a gap in the experience in terms of the depth and type of engagement with the core plane flying mechanic.

Another piece that we began exploring with this prototype was the idea of using title cards, or what would become “chapter titles” in the final game, to guide the experience. This was one major way that we found inspiration from NaissanceE: the game does a great job of presenting abstract and evocative gameplay content that is contextualized by small pieces of text outlining the sections of the game. We began with very poetic and unclear language for this prototype (further discussion of chapter titles is below in the “Art vs. Game” section), but this format and use of words in very specific, targeted moments became central to our approach.

These prototypes served as a strong initial round of content that we could build and iterate on, and following their development, we began to clarify specifics and generate a more detailed plan for the final version of the game.

Narrowing and Focusing

Around this time, we discovered a need for a very clear and concise “premise” that the game could be based around. We use the term “premise” to refer to a more easily understandable basis for which to build the game. For NaissanceE, we identified its premise as a descent into madness which was helpful for us to identify the use of a premise. A premise statement is clear, simple, and provides a concrete lens to understand often extremely vague and abstract gameplay experiences. In large part, this understandable premise is what allows the player to find meaning in their gameplay experience.

Up until this point, we had been mostly thinking about the project as being generally about the experience of hyperreality; for us, this has a lot of associations with the internet, growing up, our relationships to identity, truth, etc. But in all of our different projects on the subject to this point, we found that core identity extremely elusive and undefined. After some deliberation, we settled on the idea of doomscrolling as a premise that we could lean into. For us, it encapsulates a lot of the core experiences of hyperreality that we want to be discussing, including topics like contrast, vulnerability, nostalgia, overwhelm, and identity. Additionally, it sits in an area of hyperreality that we really wanted to criticize: the extremely commodified, capital-first world of social media. After finalizing that decision, we had a much clearer grounding from which to plan out the emotional contours and specific content of the game.

From there, we created a detailed outline of each of the sections of the game, planning out how our existing levels would fit in (and what changes we would make to them) as well as additional levels that we hoped to add. We made plans for the beginning and ending of the game as well, clarifying the fiction of the world we were creating and the diegetic bounds of the experience (with extensive discussions about how the hangar represents “reality” and who the player is playing as). An important part of this practice was detailing how each level was supposed to feel in simple terms, creating a world that would flow between states of aggression and relative kindness towards the player with an emphasis on contrast and juxtaposition. We additionally detailed how each level would engage with and develop the core mechanics and sense of challenge in the game, distinguishing between the complexity of the dexterity challenges we would present and the complexity/overwhelm of the environments.

After putting together this plan, we were able to move forward into something resembling “production”. We spent time creating and iterating on content, moving slowly into more and more playtests and refining our ideas into the final forms that they now exist in. Over time, we got better and better at restricting the scope of our conversations: we recognized a need to transition from theoretical discussions (which could stretch on for hours) into more practical decision making that gave us enough time to create the actual content. There was definitely a balance here; for example, we continued to give a lot of conversation time to planning out the ending, as we felt that this was an extremely important part of the artistic impact of the game. Production included the use of a lot of practical game development skills that we accrued throughout our time in school, including knowing when and how to rescope certain aspects of the game and finding high-impact ways to add juice and polish to the experience. And after what felt like a great deal of iterations, we finished the game.

Art vs. Game

This section will summarize the questions and considerations we had as we negotiated how to approach making a game that prioritized being art. The main points will be separated into three categories: the “game” part of what we made, the “art” parts of what we made, and a discussion on effectivity through the lens of poetry and clarity.

Experience Design – The Game

Why did we make a game?

Aside from the obvious predisposition three game design students might have to making games, part of our interest in expressing our ideas through games comes from our personal experience with games as media that has transformed our lives. People talk about life changing books, paintings, and music – often in tandem with calling them works of art – yet this discussion often only extends to games only with significant argument. We also found ourselves at a point where we wanted to make a game specifically that had impact or some greater meaning/contribution past surface level entertainment.

Games are the medium for living lives. We think that surely this means that games can have significant impact. We had also found that we wanted to engage with the idea of capitalist-hyperreality. We had made a previous prototype that sought to depict the concept of hyperreality, but that didn’t really end up saying much. This left us discussing what we wanted players to take away from this life we were trying to design for them to experience, but that it was in fact important for that experience to be something embodied, something lived.

Pedagogy of the Oppressed, by Paulo Freire

There are some critical ideas from Freire’s work that were core pillars to our design justifications. First is the recognition and understanding of the mechanisms of cycles of oppression. An oppressor oppressing the oppressed is a violent act – a dehumanizing act (chapter 1). This cycle is vicious and frequently leaves the oppressed with not much more than the desire to escape their oppressors by themselves becoming oppressors. The cycle presents a false dichotomy that advocates from a false freedom found through being the oppressor. Freire posits that one can break this cycle, find true freedom, and that ultimately, due to the nature of oppression, the oppressed is the only party that can liberate the oppressors – a profound act of love as they must first recognize that they themselves are oppressed, let go of any desire to be the oppressor, liberate themselves, then also liberate their oppressors. It’s a lot.

In our prototype titled The Tower, we attempted to depict some fundamental characteristics of hyperreality – to represent the Subjective Everything (more on that here). What we primarily found lacking in this prototype was that we do not actually have much practical experience with a pure hyperreality. Our lives – our personal hyperrealities – have been filtered through capitalism which also has a character, an oppressive character. Understanding the forces controlling the permutation of hyperreality that we live in and grew up with as oppressive led us to the idea of creating an experience in which the player can take the first step out of a cycle of oppression.

Corporate social media is an oppressive force we identified as something that typified our experience with capitalist hyperreality. This led us to the idea of doomscrolling as a metaphor and template for what the emotional experience of the game ought to be. To be clear, we were figuring out how to articulate this as we made the game. That said, what we did know from the start was that we wanted to replicate the emotional experience of doomscrolling in the form of a game and have the interactivity there mean something. The experience of doomscrolling is generally an interactive one too, which lends itself to being turned into a game, but the specific vocabulary we now have of, “we want the player to take a step out of a cycle of oppression [which will hopefully be an experience they can use to critically break down other cycles of oppression they might be in and start working to step out of that too]” was something we argued over and had to figure out on the fly.

Prioritizing the Metaphor – The Art

There are a lot of implicit expectations about games that we generally bring to our design process, such as the idea that they should be fun to play, fundamentally fair, and include satisfying outcomes. We entered our first semester pretty unconcerned about making games that conform to these expectations. Though games might generally conform to these expectations, we wanted to push these definitions and divest from the institutional and cultural demands that associate themselves with these expectations.

Considerations for making a game you want to be seen as art:

Throughout our time in college, we have spent a lot of time talking about what art is. We don’t have some catch-all set of heuristics for this, and many of our opinions are formed from impressions and personal experiences (which seems to be how the average person forms their own definition of art anyway). That said, there are also institutions that tend to arbitrate art, even if it is through the simple act of displaying a painting in a gallery. Some games have been identified as art by some institutions, but no widely accepted standard for games as art exists; hence, a lot of our discussion was colloquial in nature.

We spent time talking about how the exhibition of some artworks is a primary factor in whether a regular person would call it art, but games do not really have a standard mode of presentation that qualifies them as art in the way that a gallery exhibition might qualify a painting as art or a concert in a hall with velvet seats might aid in qualifying some music as art. Games have marketplaces which do not lend themselves to presenting their products as art.

In an attempt to take our work seriously, instead of prioritizing a “fun player experience” we strongly considered the integrity of the metaphor present in the player experience, often making decisions that would work against the game being fun. This introduced a couple of complications. One of the first things we learned in game design school is that the designer does not ship with the box (you can’t clarify your rule sheet to every person who has bought a copy of your board game; the rules must speak for themselves). Painters don’t usually ship with their paintings, but they do often at least have plaques next to their paintings and sometimes present their work at exhibitions in person too. These posts are maybe a bit more than a plaque, but we opted to treat our steam descriptions as a sort of plaque: “ terminal connection is an experimental art game about doomscrolling. You fly a plane.” We’re hoping this might help our players play our game as they might engage with art, whatever that means to them.

Why bother calling it art?

Our discussion moved to what artmaking in practice is. We discussed painters, writers, and auteurs and how their public presentation as Artists help validate their work as art. If you’ve read up until this point, you might guess that we’ve taken some guidance from this practice in how we refer to our games as art and present everything we’ve made through the name of Art Games Thesis. Predisposing your audience to be ready to consume art seems to be part of the trick to get people to understand your work as art. The other half of the equation seems to be taking your own work seriously enough to call it art.

Calling your work art doesn’t mean it’s serious, and not all serious things are art, but this was the avenue that made sense to us. We needed a mechanism to understand our work differently than how we had been taught to understand our work – we didn’t want to make a product, something that had to market well, or something that was optimized to be as engaging and addictive as humanly possible. We want to make something that would have an impact.

Gameplay was something that would be in service of an experience, in service of a metaphor. We spoke extensively about diegesis, about making what happens inside the game as internally consistent and justified as possible, so that the game itself would hold true when tested against the things we were trying to say. This meant that our efforts were spent discussing how to make something accurate, instead of our efforts only being about how to make something fun.

You might be asking, did it work? Does it say the thing? Do people get it? The answer to that is complicated. Most of our playtesters were friends and people we know. This introduces a bias of, “I need to finish this game, or at least try and play all of it”, which clashes a bit with the idea of quitting the game when you can’t take it anymore. We’ll be keeping a close eye on Steam reviews and engaging with other people in our community. We did find that in discussion with people who played the game, as we walked through the pieces of it step by step, people did seem to get what it tries to say and had some understanding of the game that lined up with what we wanted it to communicate. That said, the method of ending the game is controversial or at least non-traditional. It’s also quite hard to measure whether people felt/understood their experience as, “I have taken a step out of an oppressive cycle” as that is specific vocabulary we use that is dependent on it having been written by Friere. Things are unclear to us at this point, but our design decisions do in theory line up consistently with the metaphor we chose.

Poetry and Clarity

As a final note on attempting to create a consistent metaphor, we ran face first into the wall of clarity pretty frequently. Our disposition to making art translated to most of what we made reading more like poetry and less like a scientific paper. Which is great. Sometimes. In an attempt to bring some readability to our work, we decided to add chapter titles. Those ended up at least being poetic, but we wanted to provide some semblance of solid ground through which the player might attempt to interpret our work. In line with our decision to have a plaque accompany our work, our Steam description, which reads, “terminal connection is an experimental art game about doomscrolling. You fly a plane.” is intended to provide a clarifying lens to the player through which they can interpret the game as a whole.

terminal connection doesn’t have waypoints, a statement of the object of the game, or a line somewhere that says, “the point of the game is to decide to quit it.” You can die, and you respawn, but we don’t really identify if that means anything, and there are no explicit “you’re on the right track” indicators. In order to move between any level, you have to either fly into an invisible collider or survive long enough to beat a timer, and we disclaim none of this. All this is again in service of the metaphor. The exit button is always visible in the cockpit, and like with doomscrolling, there is no real, discrete objective presented to the player in the game. That walks the line of there being an end to the game at all, but credits do roll the moment you click that quit button.

The first thing that displays when you do quit the game is the text, “you have broken the terminal connection” which is about as clear of a, “you’ve succeeded” statement we could come up with in the context of the game. The game also quits itself if you let the credits roll for about a minute and a half, so it does have a very clear indication that it’s over in that sense. Again though, we are a bit uncertain whether people will be able to decipher the meaning we tried to encrypt into this experience. While we could have simply said, “if you can, you should step out of the cycles of oppression you’re in”, the whole point of communicating that through the medium of a game is the hope that the player might gain some embodied knowledge and experience with this problem, which might help them do something similar in other facets of their lives. While we worked towards clarifying our poetry to the extent that it was readable at all, sometimes you need things to be poetic to really feel what it means. That’s part of the thesis at least.

Challenges in the Game

Dexterity Versus Navigation

Fundamentally, games are built around challenges. Not all games have to feature difficult challenges, but all games do feature some assortment of tasks that involve tension. Early on in our discussions regarding what types of challenges we want in terminal connection, we identified our game as a sort of pseudo flight simulator with obstacle course elements on a mechanical level. As such, the two primary types of challenges we included in our previous prototypes were around navigation (finding where to go) and dexterity (getting to where you have to go). In earlier renditions of our game we featured both types of challenge, which we soon found was beyond the scope of what we had time to create. Navigation challenges and dexterity challenges require their own unique and very different sets of heuristics to design. Tackling both at once while figuring out how to make an art game was too much for this project. With this in mind, we decided to just feature one of the two. Either the difficulty was going to come from figuring out where to go (with the actual journey there being easy), or the player must always know where they should be going and the difficulty comes from maneuvering around obstacles to get there.

Making navigation the core type of difficulty felt like a strong decision as the game is centered around themes of navigating hyperreality, which is a disorienting and confusing process. We thought that the confusion brought about by navigation challenges would be in service to the metaphor. However, after more testing we realized the difficulty of designing proper navigation challenges alongside the other visual goals we had for the level. Getting rid of all dexterity challenges also made the moment-to-moment gameplay extremely bland. Navigation challenges heavily rely on consistent signposting and a clear visual language to guide the player. We really wanted to get crazy with the visual design of our levels, and in the end we didn’t want to restrict ourselves with the limitations of navigation as our core type of challenge.

Transitioning to dexterity as our core type of challenge ended up being a good decision. It allowed us to create linear levels that were easy to navigate/wayfind and allowed the player to focus more on the crazy visuals around them. It also allowed us to get really wild with what types of visuals we wanted to include as long as the contours of the space were still clear enough to know where you were going. We were also able to intermix interesting visual components into the dexterity driven obstacles. Focusing more on dexterity challenges also allowed us to create a clearer internal separation between when we were conveying meaning through visual elements, gameplay elements, or through the connection of the two.

We knew from our prototyping that an important aspect of evocative art is that it must make the viewer/player/listener feel something. It must incite a strong emotional response that is then tied to concepts, ideas, and theories. It is the emotions that then give the ideas weight and meaning. Choosing to opt for dexterity challenges allowed us to easily pace the tension in the game and keep players experientially engaged and gave room for the aesthetics of the levels to instill more emotional engagement.

Should this Game be Hard?

The discussion around difficulty was long and ever-present throughout our development process. We are still somewhat divided on this topic, but we ended up reaching a close enough middle ground at the end. The fundamental questions that this topic is based on were “should this game be fun/engaging?” and “how true to our artistic vision should we stay even if we have to sacrifice fun?”

For the first question, a core belief that we eventually landed on was that most people will only care about your game if they like it (or at the very least don’t hate it). This of course is not true for all games and all players, but it is true for a great enough majority for it to be taken under great consideration. When an experience is overly arduous, frustrating, or boring, those negative emotions tend to drown out all meaning behind the game as they stifle a player’s willingness to engage with the game’s themes or sometimes even to play at all. Players will often unsubscribe from trying to see the greater meaning of the game when faced with great displeasure alongside great disengagement.

For the second question, we knew we wanted to make this game with our artistic intent as the primary priority. We knew going in that we were willing to sacrifice what we were taught and understood as traditionally “good game design” in service of this goal.

Difficulty would arise when these two truths clashed with one another. There were often times when we felt like a more difficult and frustrating experience would better convey our artistic goals, but at the same time we couldn’t go too far or else it may make players check out and disregard the game’s underlying themes. We had to become intimately aware of the point at which the game became overly frustrating and ride that line when balancing the difficulty. There were also points that we identified when crossing that boundary of frustration was acceptable momentarily, as long as we provided enough of a payoff and lead up. Difficulty, and in particular the number of times the player dies, relates closely to the amount of time that they spend in the levels and their opportunity to take everything in. If a player blew through the level on their first try, they wouldn’t have been able to take in all that the level has to offer. Making the levels more difficult also forced the player to get more familiar with the contours and details of the level and generally reinforced the effectiveness of the artistic message. It also incentivized players to garner a greater attunement to the particular gimmicks of the plane controller and the nuances of how the different environments impacted the way you must fly.

After many attempts to ride this line of tension, frustration, and difficulty we discovered the fundamental truth that every player has a different tolerance to difficulty that we cannot fully account for. This is also the point that we still have disagreements on, but we ended up coming to a compromise on what level of difficulty is appropriate for the general audience of our game. In identifying the particularities of our target audience we have also done work outside the development of the game (posturing the game as art in our Steam store presence) to prime players for the type of experience that this game will be.

Once again, we would love to hear your thoughts in the discussion section below! Also, we have individual reflections on our experiences of the thesis as a whole that can be found here. Thank you!

Leave a comment